Abundance

The small red car stopped beside me. My outstretched arm, made heavier by my extended thumb, was getting tired. The driver was a smiling Haida woman, and as is usually the case when hitchhiking, the conversation got interesting quickly. She asked, “Did you know this place is one of the spiritual centres of the entire hemisphere?”I did not. But I would have guessed it after all I’d been through.

“The area where you’re going, K’aay Llnegaay, is one of the strongest places on the island,” she explained. “I was once walking along this road, late at night. An elderly women slowly and silently approached, and stopped in front of me. She stared into my eyes, expressionless. I wasn’t afraid. She extended her arm up and slowly pointed at me, then up to the sky, and then suddenly evaporated into an orange mist.”

We were actually at my destination, parked so we could keep speaking. She told me about how when they excavated this place for the Haida Heritage Centre, they found an ancient graveyard. “The spirits were disrupted, and every night at 3am the people living nearby could hear them chanting. The man living in the nearest house complained of them daily in his house. He wanted the ceremony hurried because they kept getting in his way. A few days later, we properly carried all the coffins down the road, to a new resting place, and they never bothered him again.”

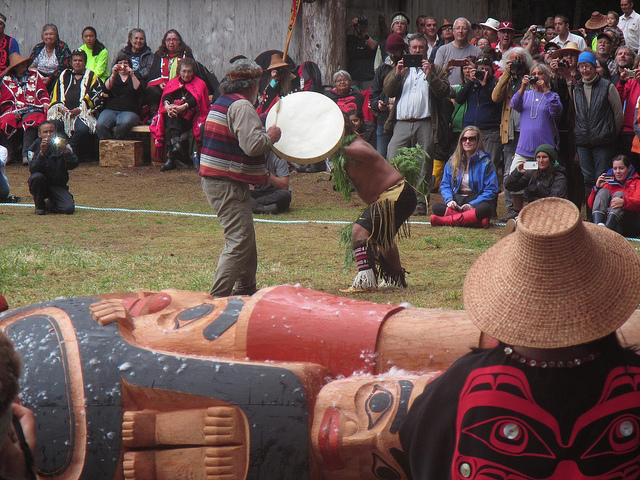

Guujaaw — probably the most important person in the modern battles I’ve written about — fights off an evil spirit during the pole raising ceremony.

I was fascinated by her tales, but we were at the Heritage Centre. I was here to listen to presentations by my friend Emily (whom I haven’t spoken to in 5 years, yet just happened to bump into in one of the remotest places in Canada) and her cohort of teachers on a university practicum learning how to adapt curriculum to local knowledge. Local knowledge being one of the many things found in abundance on Haida Gwaii.

Chris’ presentations struck me the most, discussing the mask of the Sea Foam Woman. When he’d first visited this Heritage Centre the mask hung safely behind glass; a cultural relic to be preserved and discussed, like most things in museums. When he’d attended the potlatch a week later (the same one with Barry and I) he’d seen the Sea Foam Woman mask appear on stage for a traditional musical dance performance (as shown in my video from Canada #3.5. Yes, that’s lightning in her eyes). The mask was used to act out the legend of the Sea Foam Woman. Chris explained, at that moment, he felt his narrow view of the culture blown to bits. He was witnessing for the first time a culture both historically significant, yet alive and thriving.

Watching these kids during the long summer sunset made me nostalgic for the childhood I remember lasting forever.

That potlatch feast, full of locally grown and gathered delicacies, was given free to over 1000 people. It was celebrating the raising of the “legacy totem pole” in Gwaii Haanas (literally ‘islands of beauty‘, the protected southern third of the archipelago). It was the first raising in 120 years, which we had been fortunate enough to attend during our five days of remote sea kayaking in large part due to the advice and encouragement of professional adventurers Bruce and Dave. The pole raising was a remarkable way to end our self-propelled wilderness voyage through hundreds of islands and pristine old growth forests with some of the largest trees on earth. Large trees being one of the many things found in abundance on Haida Gwaii.

Yet the only reason that Gwaii Haanas remains as such is because of the fight by the Haida, beginning in the 1970s after enshrining in Haida law that it must remain pristine in perpetuity. This potlatch featured many of the crucial people in that fight, whom I’d read so much about. Maybe a bit too much: When I met one of the totem pole carvers at a house party, I scared him by reciting the story of how he’d gotten his name (his parents took him as a newborn on a long wilderness canoe trip into Gwaii Haanas. His name is Gwaii). At this potlatch, before my very ears, I got to hear some of these famous stories told firsthand. Stories being one of the many things found in abundance on Haida Gwaii. (The potlatch lasted 11 hours).

Here’s one of them, from a retired policemen, describing a moment from the famous 1985 protest. He was ordered to arrest the protesters blockading the logging road. These protestors were not smelly tree huggers; they were the community’s revered elders. He said, with all the emotion still present from 30 years earlier, “I am very glad it was raining that day. Otherwise people would have seen the tears that were running down my cheeks. I crossed the 50 metres to the blockade. It was the longest walk of my life.”

He arrested the first elder in the line: It was his grandmother.

When I met Guujaaw, he said to me “You know, the ravens here don’t sound like those elsewhere. They speak a different raven language than others.”

Going with the flow (except when it’s towards your SLR)

If you take a look at north east corner of Haida Gwaii from above, an impossible looking needle of sand extends over five kilometres into the open ocean; befitting for a place with so many other impossibilities. This feature is called Rose Spit. Its existence captivated me purely on geography. Then I learned it happens to be the birthplace of humanity. Yes, it was here Raven opened the clam shell and the first men exited into the world. Without most of you Canadians realising it you’ve been literally sitting on this story for years on your $20 bills.

I wanted to spend my last few days on the islands hiking the two day loop to Rose Spit. We had actually been up this end of the island earlier in the trip, but without time to hike: Barry and I had driven our rental car around the reservation in Masset, looking for the Haidabucks coffeeshop. I later learned why we never found it: Haidabucks was long gone. And if you think it’s because Starbucks tried to sue them for copyright infringement (they did), well, I haven’t taught you enough. It was Haidabucks who intimidated Starbucks into dropping the lawsuit. The Haida do not let corporations push them around.

So with Barry — and more importantly, our rental car — gone I had to get myself out to the trailhead in the far corner of the island. Sometimes in life no matter how much you try to organise something, it stubbornly refuses to be. Over just two days I had arranged to hike with, and been ditched by, five different hiking partners. Thankfully it had no effect on my goal. So after a bizarre and entertaining evening which included a trio of ukeleles jamming, and freestyle rap battles between the teachers and some Haida, I got up early, unfurled my trusty thumb (which would never ditch me) and was on my way.

I made disparaging remarks about this twangy little instrument, but quickly realised I was outnumbered. Ukuleles: 3, Guitars: 0.

The hike was deeply rewarding: Because it was a muddy slog through forests and slippery logs; because I carried at least 5kg I absolutely did not need just for the sake of ‘extra training’ (I had suffered a “What would Boris do?” moment), which kept growing with all the beautiful stones I kept finding; because I stayed in a beautiful beachside hut emanating with good vibes, as evidenced by the old guestbooks bursting with ecstatic entries (including one by the two lovely girls who ditched me a day earlier); and because it was the culmination of a very enlightening and magical two weeks on the archipelago. Magic being one of the many things found in abundance on Haida Gwaii.

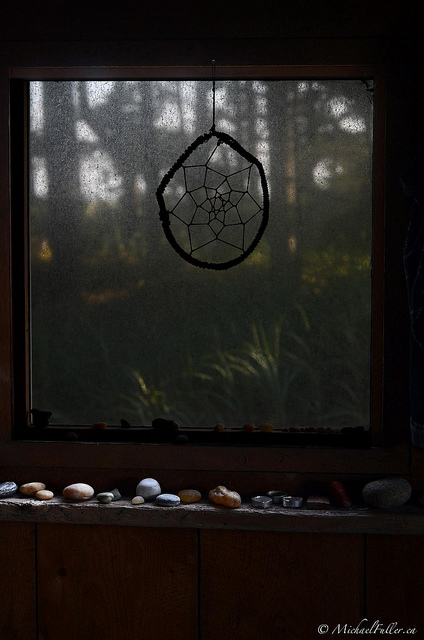

Staying alone in this hut could have been spooky, but dreamcatchers, agates, forest, and beach is a recipe for good vibes.

When I reached the narrow tip of Rose Spit, it was pure glory. The pointy tip of sand descended beneath the ocean as waves crashed into each other from opposite directions. Hundreds of birds swirled around me, feeding in the intertidal zone. I ran out on the landmass I’d only seen on Google Earth, leaving my camera set up on a tripod to capture the scene (by tripod, I mean a log). After a few minutes, I heard enormous wave crash behind me, and turned around to see my narrow bridge of land disappearing beneath waves leaping across the spit. As I stood there considering the situation, I suddenly heard in my head a perfect replay of the warning I’d been given not 24 hours earlier: “In a rising tide, the spit disappears much faster than you can run. Or even drive.” The souls of a hundred dead quad bikes haunt this spit. And so I took off through the water to rescue my camera from a watery grave.

Lyell island: Cut it. Clear it. Pave it.

With my body aching after the hike and two weeks without a bed, I remembered overhearing something about a hostel in the quiet logging town of Port Clements (population 440: actually one of the island’s largest towns). Thankfully my thumb wasn’t sore. Upon arrival at the hostel, I assumed the youngest, most dreadlocked dude in the room was one of the guests. He was the owner. Alan was an amazing dude: social worker, kayak guide, mushroom picker, world traveller, musician, and owner of one of the best hostels I’ve ever stayed in. He had hammocks, instruments, billiards, wifi, kayaks, big kitchen, a view of the inlet, and good location. (As he put it: “Grocery store downstairs; cafe across the street; pub on the nearest corner. What more do you need?”)Drumming, picking deliciously expensive mushrooms, and discussing the world was more than I hoped for; all I wanted was a roof. But when the former town mayor (his Dad) came over, my education about Haida Gwaii began anew. Dale was a miner turned logger turned mayor, and had spent the past 40 years living there. One of the first points he made was about our location. Although we were out there on the edge of the continental shelf, over the horizon from “Canada” (how they refer to the mainland), we were even more remote than it seemed: the relatively calm summer weather belied a winter so stormy and windy that it frequently ceases all transport to or from the island. People can wait weeks, including the sick or injured. With no hospital here, many have died while waiting days for airlifts.

Which makes this one of the more dangerous places to be a logger. It’s also one of the most fruitful: Dale explained that lumber forests are measured by how many cubic metres of harvestable wood they can grow per hectare per year. Compared to the average Canadian lumber forest, Haida Gwaii forests are not just double or triple as productive, but an incredible six times more. If that doesn’t make your eyes widen, read it again. But you better relax before you read this: Down at Lyell Island, where the fiercest battles between loggers and protestors were fought in the 80s and where we helped raise the totem pole, the average growth rate was even higher. It was an astonishing 23 times the average. And though Dale marvels at the decision to stop logging in what may be the most productive timber forest on the planet, he had come a long way from his roots.

Back in the 70s he came to the island with the logging giant Macmillan Bloedel, aka “MacBlo”. Employees proudly sported shirts that said “I got a MacBlo job”. MacBlo was keen to log Lyell Island, and didn’t care much for the protesters. Dale even owned a shirt that said “Lyell Island: Cut it. Clear it. Pave it.” But when he became mayor he said he was forced to examine facts: For instance, monumental cedars worth $10k each were being heli-logged. Seem like a decent price for a tree, right? Well those same trees are now cut and carved by Haida into totem poles sold for over $150k. Dale learned that heli-logging, combined with unsustainable harvest rates, were removing the trees so fast that by 2020, all the trees would be gone; the loggers jobless; the communities devastated. Dale had such conviction in this knowledge that he would eventually stand on the blockade preventing his own townspeople from going to work logging. In a community of 500 people—mostly loggers—this was a life-threatening decision. And that’s not hyperbole; he had death threats.

Dale told me one more story I’ll share with you, my ever patient readers, that exemplifies the ingenious warrior spirit of the Haida. (Ingenuity being one of the many things found in abundance on Haida Gwaii.) Currently, oil giant Enbridge and its cronies (among them, the Prime Minister) are desperately pushing against the non-Albertan parts of Canada (i.e. most of the country) for the construction of the Northern Gateway pipeline. This pipeline would bring tar sands oil from Alberta, across over dozens of First Nations lands, hundreds of fish-bearing rivers, and thousands of kilometres of pristine forests including the temperate coastal rainforest just across the straight from Haida Gwaii. It will also make the most carbon-intensive oil in the world more economically viable. During the community consultation with Haida Gwaii a few years ago, even the ‘money loving town of Skidegate’ was completely opposed to the project, and the situation for Enbridge was looking quite dire. After the public forums, the Enbridge executives met privately with the Council of the Haida Nation and local politicians. Dale was amongst them.

The Council replied, “Gentlemen, the Haida never do business on an empty stomach! Come and eat with us.”

We ate a feast of local delicacies: crab, gao, shrimp, and halibut, all served by the island’s prettiest young ladies. As they served up the final course of fresh local salmon, the servers approached only the Enbridge employees, carrying gravy boats. They asked those employees, “Would you like some crude oil on your salmon?”

All of them declined, quite confused.

After the meal, the Council spoke. “The reason they didn’t offer us any crude oil, is because they know we don’t like it on our salmon. We thought maybe you would? But it’s now clear that nobody wants oil on their fish.”

“So you can take your money and leave.”

And with that the meeting was over.

Apparently hours later, the Enbridge guys still did not understand: They thought they should have offered more money.

~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~/~^~

Obviously I’m back down under, and this update is tremendously overdue. But it’s actually only two weeks longer than it took the New York Times to publish my new friend Bruce’s article about Haida Gwaii. That puts me in pretty good company.

Hope you enjoyed my series from Canada even a hundredth as much I enjoyed traveling there. For all the latest photo adventures, visit my Flickr site.

With love,

-Mike

[…] Favorite beach: Long Beach, Haida Gwaii, because it led me back from Rose Spit on the best solo hike of my life. […]