ONE: The Hunt

AS I SHUFFLED DOWN the stairs to begin a decidedly lazy day, Uli my hotel owner greeted me with a smile. “They’ve seen one!” His eyes were wide. “You must go today, or you will miss it!”

I half-feared this would happen. My plan that day was to go precisely nowhere. My toe was black and swollen from a stubbing the previous night (Indonesian sidewalks are minefields). It was painful to walk, but this was a rare opportunity: These things only come out for a few days a year.

Uli, the still-incredibly-German owner (despite 20 years in Indonesia), pulled out his own GPS route maps and detailed instructions for an entire self-guided motorbike day trip (which would start after the hunt). “Remember to wear proper hiking shoes, because all this rain has made the trails very slippery. They’ve also brought out the leeches, which will crawl up out of the mud and into your shoes. So wear long socks.”

Oh boy, if there’s one thing I love about jungles… it’s leeches.

As it turned out a few hours later I’d be pulling blood-fattened leeches from my feet during the post-hunt coffee break with the stately and proper matriarch, Ms Imui. She runs an organic Luwak coffee farm. Luwak, as many know, is the exorbitant coffee made from beans partially fermented in the stomach of the wild civet cat.

You might also call it cat-poo coffee.

Since non-organic Luwak usually entails caged civet cats hand-fed by children kept out of school, I was happy to pay for the organic version, fresh from the cat’s butt.

But I digress. Back to the hunt:

From Uli’s hotel I set off with a German couple still channelling the spirit of the autobahn. I chased them into the looming wall of storm clouds, dodging rain drops, chickens, and school children, in order of priority.

Half an hour later we slowed in a village, and our hunting guide appeared at the road side. Without delay we motored through the narrow paths, swimming-holes, moated houses, and rice-terraced hills of possibly the most picturesque village I’ve ever seen. Then the hike began.

An hour of mini-landslides and mud-pits later, we found what we came for. Trying not to disturb such an enormous and rare life form, we carefully approached for a few photos before making the trek back. Unknowingly, I also carried three wriggly stowaways who’d burrowed through my sweaty socks to drink my sweet feet-blood.

Tender toes, landslides, leeches — was it all worth it? Probably. I love obscure treasure hunts, and rafflesia arnoldi seemed pretty obscure to me. When else does one get a chance to see the largest flower in the world?

TWO: Layang Layang

FOLLOWING ULI’S militarily-precise maps, I continued my tour de Sumatra. At one point, hours from town, I saw a familiar face cresting a hiking trail onto my road. It was an old-new local friend with whom serendipity had already intertwined my path twice before. It was remarkable to happen upon him here, kilometers from anywhere, and he guided me to a sugar shack to learn how Indo’s sweetest export is produced.

After hours of motorbiking down winding roads the width of sidewalks, through fertile mountain villages, and along striking crater-rim vistas, the sun was getting low.

In the equatorial latitudes of central Sumatra, sunsets don’t take long. So I aimed my motorbike – 150 cubic centimeters of pure power – away from the setting sun, towards ‘home’. I wove through more mountain rice paddies, soaking in the warm light and refreshing mountain air.

Then I saw something strange and confusing. What appeared to be an explosion of white winged creatures.

In the distance it looked like a flock of birds, except they were rocketing straight up into the sky. As I strained my eyes on the creatures climbing hundreds of meters high, craning my neck I nearly crashed the motorbike craning my neck. What were they? I finally noticed a clue: some fine lines shimmering after them, converging in a distant paddy.

I had to reach that field.

So I drove on, dismounted, and danced my way through a soggy, freshly harvested rice paddy. There I found my answer:

A kite competition, kompetisi layang-layang. (Note the word for ‘kite’ is a fun double word in Indonesian. My second favourite one, after lumba-lumba, which means ‘dolphin’).

Everyone there was 50% participant, 50% spectator, and 100% hilarious. One guy kept offering me coffee, which became a running joke after the third offer. Another, the organiser, conversed with me casually while holding an activated megaphone to his mouth – regardless of how close we were standing or how uninterested others might be in his half of the conversation.

The sight of simple and elegant kites gliding hundreds of meters high was captivating. But with the sun kissing the horizon I needed to burn rubber to avoid dangerous night driving. As I left the rice paddy, I was bid farewell by a familiar voice.

Amplified by a megaphone.

Get set.

[Like these photos? Check out my full photo essay, “The Wondrous Kite Competitions of the Central Sumatra Highlands“]

THREE: Father Moto-taxi

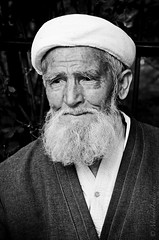

I’D REACHED THE END of my Sumatra trip. I was flying at 5:30 the next morning, and was looking for a motorbike taxi (‘ojek’) driver to bring me to the airport. My hotel owner indicated her elderly friend could be convinced. So I asked if he was an orang ojek (‘moto-taxi man’).

“No,” they laughed, “he’s Bapak Ojek!” (‘father moto-taxi’).

In the wee-hours of the next morning, before dawn has even crossed anyone’s mind, we began our 30 minute trip – which, oddly, he thought would take an hour. I quickly found out why.

Five minutes into the trip, we were getting speed wobbles – from our lack of speed. If safety was this old man’s concern, I thought, perhaps he’d be wise to fix his motorbike’s broken head and tail lights. We were puttering along in perfect stealth mode, invisible to cars in the unlit streets until seconds before collision when they swerved around us.

“Could you speed up?” said no foreigner to any Indonesian, ever. Except me, to Bapak Ojek. We almost hit 30 km/h for a whole minute. Then he slowed again.

“I’m cold,” he complained. Yes, it was a frigid 24˚C that morning, and he only had a jacket on (backwards of course; it was the style at the time).

Still too early even for the petrol station attendant.

Eventually, we made it there unharmed; I saved taxi fare; and I caught my flight.

And like most frugality-induced experiences: the $7 I saved wasn’t the point. Riding on moto-taxis is a lot more fun (aka dangerous), quicker (except this time), and the drivers poorer (not in skill but in wealth. So your money means a lot to them).

Maybe now, Father Moto-taxi is cruising around with a working tail-light.

<-> <-> <->THESE STORIES ALL take place in central Sumatra, the heartland of the Minangkabau people. They are a rare matrilineal culture – passing property, family name, and wealth via the female line. But as one of their proverbs illustrates – “the fingertip is formed together by the skin and the nail” – men aren’t relegated too much.

In the basic family clan, the eldest woman is in charge, and the highest ranking male is not her husband, but her eldest brother. He ensures his sister’s children are given good education and marriage prospects.

The Minang are actually the largest such matrilineal culture in the world – noteworthy, on its own. But wait! – there’s more. They’re regarded highly within Indonesia for being a cosmopolitan, intellectual culture of poets, writers, scholars, and important contributors to the independence movement against Dutch colonials.

And to many tourists and locals: As the creators of Padang food. The glass and aluminium shelves of food behind lacy curtains are as ubiquitous to Indonesians as Chinese Restaurants are to us westerners. And almost every tourist has mimed their way to a meal of cold curries, spicy eggs, or deep fried fish served on a (thankfully) fresh bed of rice.

This over-representation of Minangs amongst the educated classes (and restauranteurs) is no accident. There is a uniquely Minang tradition called merantau, which means “find your way in the world”. This tradition encourages teenage boys to leave their hometown to gain experience and education elsewhere – so that they can return as “wise and useful” adults. This helps them to run their own family clan, or their local community (as a member of the “council of uncles”), upon return.

<-> <-> <->I CAN’T HELP BUT think that the last 7 years of my life – especially the last 4 months – has been my ‘merantau’. The Experiences on this very website have brought you along on some of my journey and its challenges: From getting conned in Zambia, to battling with night shift and bogan coworkers in an underground mine, to getting arrested in China.

But instead of opening a restaurant – I started the ONE Project. You might call it my attempt at being ‘wise and useful’. Now all I need is an invite to a council of uncles.

-Mike

p.s. Don’t forget to check out my kite competition photo essay. Now, please enjoy some photos from other Sumatran motorbike trips:

This rice farming woman in the beautiful Harau Valley has created an elaborate system of strings, streamers, and cowbell-like cans. She just pulls one string and scares away the birds from her rice field.

Taken during the Pacu Jawi festival, where villagers race bulls, surfing behind them on wooden plows. Biting the tail makes the bulls run faster.